Thursday, November 09, 2006

EM Woods: "Democracy as the Ideology of Empire" posted by Richard Seymour

If you can get a copy of Colin Mooers' edition of essays entitled The New Imperialists: Ideologies of Empire, it is worth shelling out if only to have a look at the essay on Michael Ignatieff and Ellen Wood's account of democracy and empire. I offer a few notes on it, because it gets to the heart of what I think unites the pro-war left with the neocons and right-wing clash-of-civlisation theorists. For Wood, the ideology of empire was succinctly expressed by the statement signed by sixty academics after 9/11 "What We're Fighting For: A Letter From America", a title that perhaps consciously mimicked the old 'Why We Fight' series from World War II. Signed by people as diverse as Francis Fukuyama, Michael Walzer and Samuel Huntington, it issues "five fundamental truths" that could have been written by any Euston Manifesto devotee, including the wisdom about all humans being free and equal, naturally seeking rational inquiry, desiring a state that protects and nourishes them, requiring freedom of conscience and ruling out killing in the name of God as the most unGodly act imaginable, a betrayal of the universality of religious faith. The statement asserts that the war on terror is a "just war" because it is not a war of "aggression and aggrandisement" and so on.

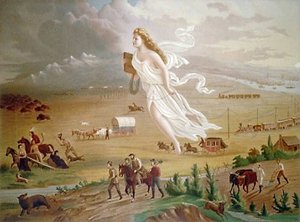

If you can get a copy of Colin Mooers' edition of essays entitled The New Imperialists: Ideologies of Empire, it is worth shelling out if only to have a look at the essay on Michael Ignatieff and Ellen Wood's account of democracy and empire. I offer a few notes on it, because it gets to the heart of what I think unites the pro-war left with the neocons and right-wing clash-of-civlisation theorists. For Wood, the ideology of empire was succinctly expressed by the statement signed by sixty academics after 9/11 "What We're Fighting For: A Letter From America", a title that perhaps consciously mimicked the old 'Why We Fight' series from World War II. Signed by people as diverse as Francis Fukuyama, Michael Walzer and Samuel Huntington, it issues "five fundamental truths" that could have been written by any Euston Manifesto devotee, including the wisdom about all humans being free and equal, naturally seeking rational inquiry, desiring a state that protects and nourishes them, requiring freedom of conscience and ruling out killing in the name of God as the most unGodly act imaginable, a betrayal of the universality of religious faith. The statement asserts that the war on terror is a "just war" because it is not a war of "aggression and aggrandisement" and so on.It is simple enough to dispute all of the claims made for US imperialism in the statement, but the question is why many people, apparently intelligent people at that, are willing to believe that the empire embraces the values they espouse. For Wood, capitalism is the source of this ideology: in the first instance, because does not depend upon formal inequalities, but rather thrives in formal equality of labour. It can therefore coexist with liberal democracy in a way that class systems based on formal inequalities cannot. Since capitalist ideology cannot invoke inequality as a principle, since its ideological appeal is precisely that it affords various kinds of equality (of rights, opportunities etc), it has to resort to some unique strategies for legitimising domination and aggression. In the first instance, colonial settlement was justified as development (you can still see this ideology in official apologias for Zionism, in which the settlers purportedly made the desert bloom). This can be found in More's Utopia, (see chapter two of Ellen Meiksins Wood and Neal Wood's A Trumpet of Sedition for an exposition of this interpretation), and the earliest justifications for English imperialism in Ireland involved the right to sieze even occupied land if it wasn't being utilised fruitfully enough. The Lockean system of property rights formalises their basis in productive and profitable use of property. Thus, in the discourse of rights, the question of domination and rule was sidestepped.

Further, in colonising overseas, one simply applied to the colonial territories the same logic that one applied domestically: the new capitalist principle in which all property claims that were not profit-based were now subordinate to those that were. But this would soon become less useful. In the 20th Century especially, formal colonisation proved to be less apt for capitalist needs than informal networks of domination initiated by political interventions, effected through market transactions but sustained through an unprecedented level of military build-up and violence. The first object of the American capitalist empire is to ensure free access to all markets for capital, (especially American capital), legitimised as "openness" and "free trade". But since the openness and freedom is all one-sided, this does not entail a properly integrated world economy. Quite the contrary: Western economies sustain tarrifs and blockades, regulations on the movement of labour and competition from low-cost economies. It is advantageous to capital to maintain this system, and so it needs "not a global state, but an orderly global system of territorial states" sustained through the principle of 'sovereignty'. Wood suggests that as citizenship in capitalist society "masks" relations of class domination, so sovereign status "masks" imperial domination.

Further, in colonising overseas, one simply applied to the colonial territories the same logic that one applied domestically: the new capitalist principle in which all property claims that were not profit-based were now subordinate to those that were. But this would soon become less useful. In the 20th Century especially, formal colonisation proved to be less apt for capitalist needs than informal networks of domination initiated by political interventions, effected through market transactions but sustained through an unprecedented level of military build-up and violence. The first object of the American capitalist empire is to ensure free access to all markets for capital, (especially American capital), legitimised as "openness" and "free trade". But since the openness and freedom is all one-sided, this does not entail a properly integrated world economy. Quite the contrary: Western economies sustain tarrifs and blockades, regulations on the movement of labour and competition from low-cost economies. It is advantageous to capital to maintain this system, and so it needs "not a global state, but an orderly global system of territorial states" sustained through the principle of 'sovereignty'. Wood suggests that as citizenship in capitalist society "masks" relations of class domination, so sovereign status "masks" imperial domination.There is nevertheless a real disjuncture between the economic needs of capital, which are globals, and the political force that sustains it, which is localised. And precisely because it falls to local nation-states to manage these procedures, because it does not involve direct territorial expansion and annexation, it requires a military force bigger than any empire in history - but it also needs an ideology to support a series of open-ended "interventions" and objectives. Since, as I mentioned, principles of inequality are unavailable, the ideological resources that can be mobilised in service of such aggression are restricted to democratic and egalitarian ones. This comes at the same time that "behind the scenes, some prominent neoliberals are admitting ... that the future we are looking forward to is one in which 80 percent of the world's population will be more or less superfluous".

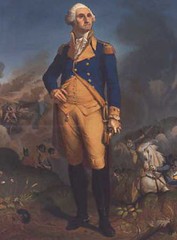

The new imperialists therefore appeal to a specifically American conception of democracy (on this, see Wood's Democracy Against Capitalism), one formed during a ruling class fight to prevent the American revolution eroding their privileges, to make democratic citizenship subordinate to a hierarchy of economic interests. In this process, the majority had to be fragmented to prevent it from achieving state power and coalescing into an overwhelming force that might be able to challenge the ruling class power. Popular sovereignty had to be filtered through a representative system that was designed to favour large landowners and merchants, with institutions not subject to direct election (Senate and presidency) and some not subject to election at all. The introduction of a strong presidency was precisely a means of avoiding democratic accountability. "We are well prepared," says Wood, "to view class power as having nothing to do with either class or power. We are educated to see property as the most fundamental human right and the market as the true realm of freedom." Political rights are passive; citizenship is passive, individual and largely private. It is an extremely useful conception of democracy in which endless strategies can be devised to marginalise and exclude the masses, thwart majorities, and reduce the scope of democracy. The doctrine that such a framework exudes contributes to the conviction that the West, particularly America, is in possession of the answers, the magic formulae, and other societies that do not possess these are inadequate, lacking and, if they get uppity, in need of an ass-kicking and Americanisation to prevent them becoming uppity again. In the past, racism was made as an open appeal, precisely where the incongruity of empire's ideological claims and the means by which it purported to pursue them was most obvious: (ie, yes we're all equal, but those guys are backward and in need of tutelage etc). The anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles of the 20th Century have made it difficult to make such appeals, but they still resurface, even if they are not usually made explicit.

The new imperialists therefore appeal to a specifically American conception of democracy (on this, see Wood's Democracy Against Capitalism), one formed during a ruling class fight to prevent the American revolution eroding their privileges, to make democratic citizenship subordinate to a hierarchy of economic interests. In this process, the majority had to be fragmented to prevent it from achieving state power and coalescing into an overwhelming force that might be able to challenge the ruling class power. Popular sovereignty had to be filtered through a representative system that was designed to favour large landowners and merchants, with institutions not subject to direct election (Senate and presidency) and some not subject to election at all. The introduction of a strong presidency was precisely a means of avoiding democratic accountability. "We are well prepared," says Wood, "to view class power as having nothing to do with either class or power. We are educated to see property as the most fundamental human right and the market as the true realm of freedom." Political rights are passive; citizenship is passive, individual and largely private. It is an extremely useful conception of democracy in which endless strategies can be devised to marginalise and exclude the masses, thwart majorities, and reduce the scope of democracy. The doctrine that such a framework exudes contributes to the conviction that the West, particularly America, is in possession of the answers, the magic formulae, and other societies that do not possess these are inadequate, lacking and, if they get uppity, in need of an ass-kicking and Americanisation to prevent them becoming uppity again. In the past, racism was made as an open appeal, precisely where the incongruity of empire's ideological claims and the means by which it purported to pursue them was most obvious: (ie, yes we're all equal, but those guys are backward and in need of tutelage etc). The anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles of the 20th Century have made it difficult to make such appeals, but they still resurface, even if they are not usually made explicit.For instance, take Bush's recent claim that if America leaves Iraq then the evil-doers will take control of the oil and use it to blackmail the West into abandoning allies and so on. This bears two implicit claims: that America promotes democracy and peace, and that any government that ensued without American guidance would be undemocratic, lawless, violent, threatening etc; and that because of this, it is in America's gift to decide what must happen to Iraq's human and natural resources. Hundreds of thousands of deaths are simply the price that 'we' must pay (although 'we' do not pay it) for ensuring that these resources remain in our hands. This is the consensus, from Madeleine Albright to Donald Rumsfeld, from Samuel Huntington to Christopher Hitchens.

There are, by the way, some invaluable critical resources on American democracy here.